More than a year before the 2020 U.S. Senate race, incumbent Susan Collins and her likely Democratic challenger, Sara Gideon, have amassed nearly $13 million in their campaign war chests.

The race is likely to set records for spending as Collins and Gideon have already collected nearly what was spent in 2008, which is the most expensive U.S. Senate race to date in Maine.

But one potential third-party candidate has already resolved not to accept any campaign contributions. Tiffany Bond, a family law attorney in Portland, has declined every donation made to her candidacy and suggested it instead be redirected to Maine businesses.

“If someone’s giving you a million dollars, they’re not giving you a million dollars because they think you’re cute or they just enjoy your policy. They want influence,” Bond said.

Bond, 43, made a name for herself in 2018 running for the U.S. House of Representatives in Maine’s 2nd congressional district. She self-financed a campaign of less than $800 and finished third among four candidates with 5.7 percent of the vote behind Jared Golden, who received 45.5 percent, and incumbent Rep. Bruce Poliquin, who was ahead with 46.3 percent of the vote after election night.

Poliquin ultimately lost the election to Golden, after the 16,552 voters who selected Bond as their first choice were redistributed to their second-pick candidate under the state’s new ranked-choice voting system. Golden picked up more than 10,000 votes during the second tally, while Poliquin added less than 5,000.

Bond could again shake up the outcome of an election, if she decides to run for U.S. Senate. The chances of her running are “extremely likely,” she said.

As an Independent, Bond needs to collect between 4,000 and 6,000 signatures by the spring to appear on the ballot. Her challenge, however, will be gaining name recognition in a race stacked with female candidates who are well-financed and already spending money, said James P. Melcher, a professor of political science at the University of Maine at Farmington.

“Name recognition is the name of the game. It’s not that you can’t have no money, but you need a little to get recognized,” Melcher said.

The 2020 Senate race is on track to break state campaign finance records, with candidates just $1 million shy of the $14 million raised during the 2008 Senate election, according to Federal Election Commission records. In that race, Collins spent $8 million to defeat Democratic challenger, U.S. Rep. Tom Allen.

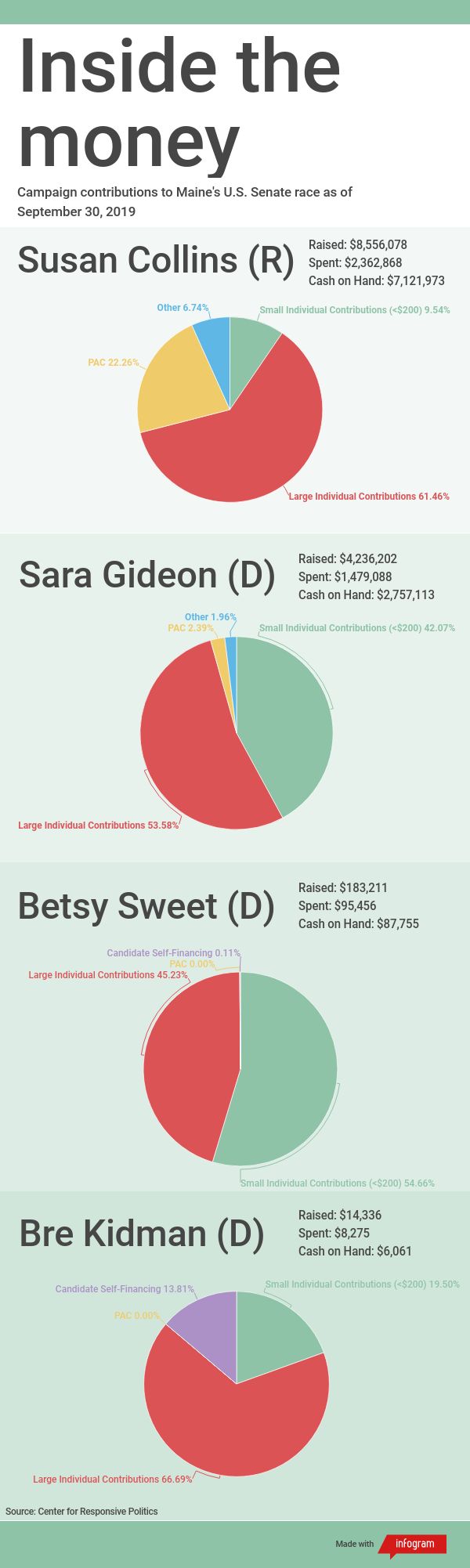

Collins, a Republican, has already raised $8.58 million for the 2020 contest. Gideon, a Democrat who is Speaker of the Maine House, raked in $1 million in the first week of her candidacy and raised $4.25 million by the end of the first quarter on September 30, according to FEC filings.

Gideon’s challengers in the March Democratic primary lag far behind in fundraising. Her closest competitor, Betsy Sweet, raised $183,000.

Paying for partisanship

Bond looks unfavorably on the glut of money flowing into the race.

“I fundamentally think money in politics is icky. It’s very corrosive,” Bond said. “You’ll see me be critical of campaigns like Sara Gideon’s where we put out a plea for money, so that we can afford to put out more pleas for money, so that we can put out even more pleas for money so that at the end we can buy really bad commercials.”

“I fundamentally think money in politics is icky. It’s very corrosive,” Bond said. “You’ll see me be critical of campaigns like Sara Gideon’s where we put out a plea for money, so that we can afford to put out more pleas for money, so that we can put out even more pleas for money so that at the end we can buy really bad commercials.”

The 2020 election is unique in how early candidates are spending money. Melcher could not recall an election when candidates were buying television advertisements this early in the campaign.

Bond said she hasn’t announced her candidacy for the Senate yet because she doesn’t believe it would be fair to her family, her law practice or voters to be actively campaigning for longer than a year.

Rather than inject money into what she sees as political theater, Bond encourages her more than 44,100 Twitter followers and potential supporters to donate to Maine classrooms or shop at Maine businesses and leave her hashtag “Maine Raising” on the receipt.

In April, Bond supporters donated using #MaineRaising to help a Belfast Area High School teacher buy two plyo boxes for the school track and field team at a cost of $407. Another supporter left a message during checkout supporting Bond for senate on a Maine Etsy merchant’s website on a $14.95 purchase.

Bond has no idea how much money the #MaineRaising campaign has put back into the state economy or every instance in which it has been used since it started in late 2017. The only way #MaineRaising comes back to Bond is if someone tweets an image of the receipt or if a business owner looks up the hashtag and connects with her.

Bond contends that the millions going into the campaign could be used for “something better.”

“We could take that same amount of political energy and money and say: No one has to be food insecure this year or nobody has to pick between food and heat this winter,” Bond said.

While some prominent national candidates have rejected donations above a certain dollar amount or the support of political action committees, known as PACs, Bond is an outlier in saying no to all outside money. She said even grassroots campaigns that rely on small individual donations “borders on abuse” because it asks individuals and families to continuously reach deeper into their pockets to sustain a campaign.

When Bond was a child growing up in Washington state, her parents would host fundraisers for Republican candidates and, as a teenager, she was a state officer in the Young Republican Federation. Since then, she has dropped all connections to political parties — vowing to caucus with whatever party is in the majority, if elected — and their pleas for donations.

A tweet by Politico reporter Burgess Everett of a campaign contribution email from the National Republican Senatorial Committee on behalf of Collins on the anniversary of her vote to add Justice Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court was recently retweeted by a Bond follower on Twitter.

“The Left has raised millions trying to unseat me and my Republican colleagues. We are counting on your support so we can keep fighting for our shared conservative values,” the email reads, before offering four-fold matching on donations made in the next 24 hours.

The rhetoric of the parties competing for donations props up an entrenched two-party system and fuels partisanship on topics that should not be partisan in the first place, Bond said.

“It’s all about the money and hyping up what the other side said,” Bond said. “Because we have the money and the super-entrenched points, we’ve just created this two-party, name-calling, hysterical, awful world. And, it’s totally unnecessary.”

Bond’s denunciation of partisanship in Washington is a message that could resonate with Maine voters, Melcher said. But Collins has plenty of examples of when she has reached across the aisle to work with Democrats in the Senate, even if its regularity has decreased under President Donald Trump, he said.

Recalculating the ballot

The wild card in the 2020 race is ranked-choice voting.

Maine used ranked-choice voting for the first time during the 2018 election and Gov. Janet Mills (D) allowed a bill to become law in September to expand its use to presidential primaries and general elections.

It’s all about the money and hyping up what the other side said. Because we have the money and the super-entrenched points, we’ve just created this two-party, name-calling, hysterical, awful world. And, it’s totally unnecessary.”

— Independent Senate candidate Tiffany Bond

Ranked-choice voting gets rid of the worst part of running as a third-party candidate, which is the dismissal of one’s opinions and the anger of constituents who believe the candidate is “taking” votes away from a major party candidate, said Rob Richie, president of FairVote, a nonpartisan organization working on electoral reform at the national and state level.

On a ranked-choice ballot, major party candidates have to consider how to position themselves to be the second or third choice to a lesser known candidate in order to receive their votes as the field is narrowed. This often means having earlier, harder policy discussions on the issues that are resonating with third-party candidate’s voters, Richie said.

“It really is a solution to a limitation on choice and a limitation on dialogue,” Richie said.

Maine voters are already “ticket splitters,” meaning they do not vote the same party all the way down the ballot, Melcher said. The best example of this was the 2008 senate race where Mainers elected President Barack Obama and Collins on the same ballot.

It will be interesting to watch if ranked-choice voting increases the number of votes going to third-party candidates, Melcher said.

He predicted voters may become more comfortable with selecting a third-party candidate and using their first choice vote as a way to send a message to the major parties. But even with ranked-choice voting, he predicted that Bond would not receive more than 10 percent of the vote next November.

Bond is not the only third-party candidate. Lisa Savage of the Green Independent Party has already announced her candidacy in the senate race and begun campaigning.

Where Bond still needs to gain ground is in making her views on topics other than campaign finance known, Melcher said.

Violence, climate and healthcare are three major topics that need bipartisan action, Bond said.

“Right now, action on climate change, where I stand, would actually be way liberal, but it’s not — it’s that we haven’t budgeted and acted appropriately and now we’re in a position where we’ve got dues to pay because we didn’t do it for the last 30 years,” Bond said.

Having a habitable planet that can be passed down to her two young sons is as basic as paying the mortgage on her home to make sure her family continues to have a place to live, Bond said. The same goes for addressing gun violence as her 6- and 8-year-olds practice lockdown drills at Portland Public Schools.

“My youngest cries about it. I picked him up one day from school … he holds me really, really tight and says, ‘Will you come pick me up if there’s bad men?’ and it just breaks your heart,” Bond said.

Bond did not plan to run for Congress until 2017, after Poliquin voted on multiple bills that made her job as a family law attorney more difficult, including the large overhaul to the U.S. tax code.

The tax code changes affected alimony, which a disproportionate amount of Mainers receive upon divorce due to the high cost of childcare and comparably low wages in the state, which can take one parent out of the workforce for a period of time, she said.

“I’ve had the pleasure and displeasure of taking those federal laws and pulling them down and saying, ‘OK, well this is what tax code means when you’re actually working with a family,’ this is how tax code actually implicates people,” Bond said.

When she interviewed campaign managers in 2017, however, all of them had the same “formula” to win: raise money to make advertisements that attack the opponent. She couldn’t stomach it.

“The job interview is antithetical to the candidates we want,” Bond said. “I want a Congress that works together — and I don’t mind if they’re more liberal or more conservative than me — I want them to genuinely make good law.”

A year ago, political observers didn’t think Bond would even register as a percentage of the vote for the 2nd congressional district, let alone have enough influence to bump the incumbent out of his seat.

Now a year out from the 2020 election, with more than 44,000 Twitter followers and the strategy of ranked-choice voting coming into play, Bond could play a pivotal role in what promises to be one of the highest profile 2020 Senate races — all without raising a dime.

For more information on the candidates:

- Follow @SenatorCollins on Twitter

- Follow @SaraGideon on Twitter or Gideon’s campaign website

- Follow @TiffanyBond on Twitter or Bond’s campaign website

- Follow @BetsySweetME on Twitter or Sweet’s campaign website

- Follow Bre Kidman @BeeKay4ME on Twitter or Kidman’s campaign website

- Follow Lisa Savage at @LisaForMaine on Twitter or on Savage’s campaign website